The last article “The Coming of Mammals – Part I” explored the emergence of terrestrial vertebrate life in the mid-Carboniferous, the rise of amniotes from the primitive amphibians, and their diversification into synapsids and sauropsids, the progenitors of mammals and reptiles respectively. We pick up our story at the beginning of the Permian Period, following the Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse, when the synapsids had started dominating the landscape.

With the dawn of the Permian Period, the major landmasses of the world were joined together to form one giant continent that straddled the equator called Pangaea. About this supercontinent lapped the “universal sea” Panthalassa. The collapse of the rainforests of the Carboniferous Period meant that plants adapted to that climate slowly died out and were replaced by seed ferns and the earliest conifers.

Among the terrestrial animals changes were taking place as well.

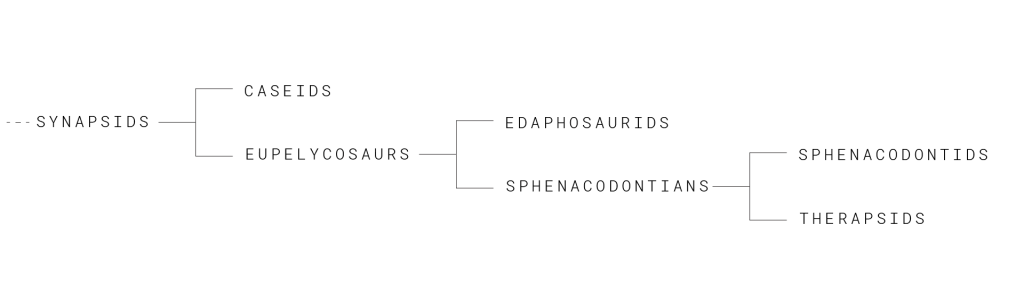

Following their split with the sauropsids, the synapsids were now beginning to evolve and diversify. Gaps in the fossil record in this period, along with several extinction events, make it difficult to follow the evolutionary lines extremely closely. However, the first herbivorous amniotes, the Edaphosaurids, evolved in this time, splitting off from the carnivorous Sphenacodontians (such as Dimetrodon).

I know, I know. A lot of big words. I’m happy to dash over this section if you will permit me and bring up the next important stop on this prehistoric train ride through mammalian evolution – the rise of the therapsids. I will add a quick note here to say that all the lineages from the synapsids to the Sphenacodontids were formerly called pelycosaurs. This word has now fallen out of favour for the more accurate term “stem mammals.”

275 million years ago, in a world dominated by stem mammals, rose the therapsids. The shadows on the wall were now starting to take a slightly more mammal-like shape. They stood with their legs positioned more vertically beneath their bodies, compared to the sideways sprawl of reptiles and amphibians. This would have resulted in the later therapsids walking more like present-day mammals with their feet underneath their bodies than with the zigzagging gait of their stem mammal ancestors. Their teeth were differentiated for the tasks of cutting, tearing, and chewing unlike the conical dagger like teeth of reptiles. By the middle of the Permian Period, the therapsids had outcompeted and replaced the stem mammal groups as the dominant terrestrial vertebrates.

The therapsids themselves split into several groups, evolving over time to give rise to the dinocephalians, dicynodonts, and the sabre-toothed gorgonopsians (not to be confused with the sabre-toothed cats that would not evolve for hundreds of millions of years still). These therapsids evolved and flourished through the Permian Period and were the dominant carnivores and herbivores on land. By the Late Permian, another group of therapsids appeared in the fossil record – the cynodonts. These therapsids were markedly smaller than their ancestors, growing to about 5 feet at a maximum but many were significantly smaller.

Everything was going swimmingly for the therapsids. Until it wasn’t.

The end of the Permian Period and the Paleozoic Era was marked by the most severe known extinction event in Earth’s history. While the exact cause for the extinction is uncertain, it is widely believed to be catastrophic volcanic activity that flooded large parts of Russia with basalt lava. Sulphur and carbon dioxide, released in massive quantities to the Earth’s atmosphere resulted in sky-rocketing global temperatures and the oceans becoming dangerously acidic. The power of the eruptions burned oil and coal deposits, adding even more carbon dioxide to an already teetering atmospheric balance.

This extinction, known as the Permian-Triassic Extinction Event, or the Great Dying (a much cooler name, in my opinion) resulted in the disappearance of over 80% of marine and 70% of terrestrial species. Ecosystems and food chains collapsed. The heavyweights of the Permian Period vanished under its settling ashes. Gone were the gorgonopsians and the early therapsids. Only a handful remained, including the cynodonts, and in the initial stages of the Triassic Period they continued as the dominant terrestrial vertebrates. But this dominance, enjoyed since the splitting of synapsids from sauropsids all those millions of years ago, was coming to an end.

The threat did not come from another, more specialized group of therapsids, but from a group of sauropsids who had flown mostly under the radar in the preceding ages. They were called the archosaurs, and they took a stranglehold of life on land in a WWE-inspired event known as the Triassic Takeover. These reptiles, much better adapted to conditions following the P-T Extinction Event, moved rapidly to conquer ecological niches, and dominate food chains. The outgunned therapsids faced two choices – go extinct or evolve to fill niches that were not in high demand among the archosaurs. Most therapsids promptly took the first option and disappeared from the fossil record.

The cynodonts, however, gave up most of their ancestral roles in exchange for being small enough to slip under the noses of the archosaurs. They became nocturnal, hunting in the Triassic nights, or burrowed – a transition known as the nocturnal bottleneck. Meanwhile, in the daylight lands of the Triassic, the archosaurs were evolving into titanic proportions. From this once obscure group of sauropsids came the crocodiles and the dinosaurs who would rule the Earth for the next 160 million years.

Beneath their feet, scurrying about in the underbrush, the cynodonts were undergoing an evolution of their own. Insignificant at the time and barely acknowledged for millions of years, the very first mammals appeared on Earth under the stars of the Triassic.

I hope you found Part II of the The Coming of Mammals interesting! Finally, after journeying with terrestrial tetrapods for hundreds of millions of years, we come across the first mammals appearing on Earth. Part III and the final edition of this series will see the story of mammals from the Triassic Period to you, the intelligent(?) present-day ape reading this sentence. However, I will take a quick detour between this and Part III to slip in an article on the Nocturnal Bottleneck which lays the platform for traits which are diagnostic of the mammals of today – so keep an eye out for that!

Leave a comment