It’s warm-blooded, it’s furry, and it drinks milk.

Most people will immediately identify this creature as a mammal. You and I are mammals (unless this is being read by a lizard that has transcended the bounds of its species, gained mastery of technology, and fluency in the English language – in which case you are a reptile), the dog sleeping on your couch is a mammal, and the thousands of strangers’ cats that populate your Instagram are also mammals.

Today, mammals are ubiquitous. They range from tiny shrews and miniscule bats no larger than your thumb to elephants, the largest extant animals on land, to blue whales, the largest animals to have ever existed on this planet. They can fly, glide, swim, and burrow. They run, hop, climb, and do taxes. They can survive in some of the harshest environments on Earth – from scorching deserts to frozen wastelands to post-lunch meetings on a Wednesday afternoon.

But where did mammals come from? How did our ancestors survive the age of the dinosaurs and what led to the explosion of mammalian lifeforms after the cataclysmic demise of the great reptiles at the end of the Cretaceous Period?

Well, to find the answers to those questions and to understand the fascinating story of mammalian evolution, let’s wind the clock back 363 million years to the beginning of the Carboniferous Period in the latter half of the Paleozoic Era. The northern and southern giant continents of Laurussia and Gondwana, among with smaller intervening landmasses, were coming together to form the gigantic supercontinent Pangaea and the planet was a hubbub of biological and tectonic activity.

Vertebrate life thus far had been restricted to the world’s oceans. Plants had slowly crept onto land and flourished but were still far from being trees as we know and recognize them. But for the first time in history the vegetation of the planet was starting to look similar to what it is today. Fish had started experimenting with growing limbs, no doubt miffed about being beaten in the race to colonize land by plants which are not particularly known for their mobility. As a result, the very first tetrapods (tetra – four : pods – feet) dragged themselves bodily onto terra firma during the Carboniferous. This was a monumental achievement in the evolution of life.

There was, however, a small problem.

These first tetrapods, in the manner of their fish relatives, were still egg laying animals. Eggs, once laid, cannot be exposed to sunlight and air, or they would dry out and kill the growing embryo within. Therefore, these first tetrapods were confined to the fringes of waterbodies, unable to foray further inland as they needed to lay their eggs in water and led an amphibious lifestyle much like the frogs of today.

But hold on, I hear you exclaim, eggs don’t need to be kept in water. They keep perfectly well in normal conditions like in a carton on my countertop. You are quite right, of course. The reason that farmers are not required to dunk their prized egg-laying hens into pails of water is because of a rather considerate evolutionary split that happened among the tetrapods 330-320 million years ago, several million years after their colonization of land.

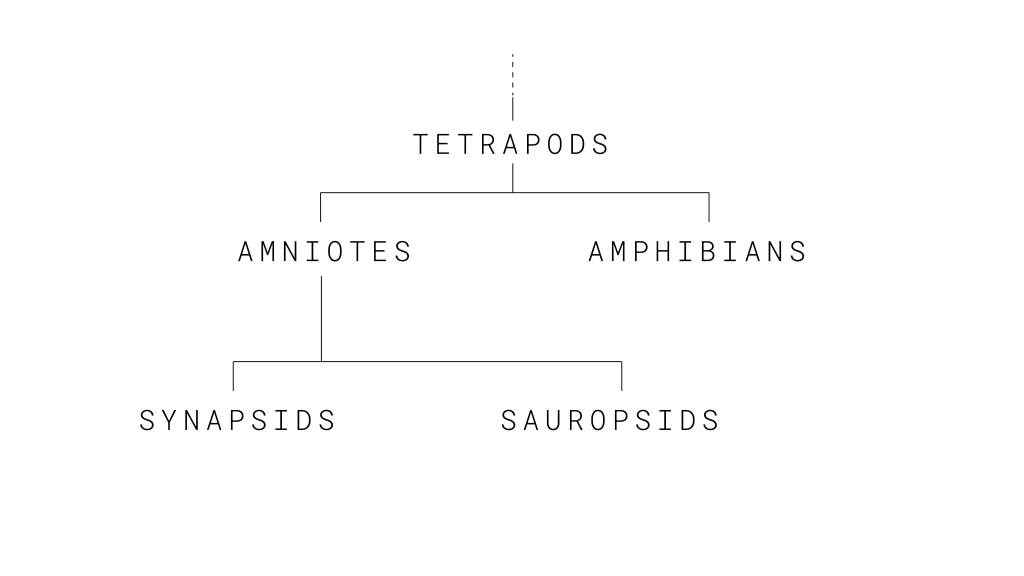

This split gave rise to a group of animals which are called the amniotes. The key defining feature of this group was an egg which had a protective shell and a series of internal membranes that retained water but allowed gas exchange. Being able to create and hold the ideal conditions for the embryo within the egg itself freed the amniotes to leave the water behind and plunge further into a brave new world than any had ever gone before (save, of course, the plants). This moment in evolutionary history is important as the diverging point of two major tetrapod groups – the wandering amniotes who would give rise to reptiles, birds, and mammals; and the amphibians who remained (and to this day remain) in close contact with water.

By the late Carboniferous, the amniotes had further undergone another divergence, splitting this time into synapsids, the distant progenitor of mammals, and sauropsids who would become reptiles and eventually birds. The synapsids are identified in the fossil record by a second opening in its skull behind the eye orbit called the temporal fenestra, which is believed to be an attachment site for jaw muscles. This split denotes the last common ancestor of reptiles and mammals, the amniote reptiliomorpha, and from here on these two enormously influential terrestrial vertebrate groups will forge their own paths through the uncertain maze of evolution and wage an unending war for the dominance of land.

An interesting point to note, if you are still with me, for which I will be pleasantly surprised, is that some synapsid species that would arise after this split still looked rather like reptiles. The sail-backed Dimetrodon, for example, looks like a primitive dinosaur and these animals were, in fact, called “mammal-like reptiles” in olden literature. However, it is now believed that the mammalian and reptilian lineages split from amniotes and evolved parallel to one another. All synapsids, including living mammals and the suspiciously dinosaur-like Dimetrodon, are more closely related to one another than any are to reptiles.

Shortly after the split of synapsids and sauropsids, the Carboniferous Period came to an end with an extinction event called the Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse which also signalled the beginning of the next Period, the Permian. The rainforest collapse is significant in that it reduced the previously sprawling rainforests to isolated pockets with the land in-between being dry and arid. Here the amphibians, once the dominant force, faltered. Desiccation in the glaring sunlight meant they could not travel between the fragmented patches, and many went extinct. The amniotes, however, true to their boy scout training of always being prepared, diversified, and flourished.

In particular, the synapsids latched onto the conditions of the Permian Period and grew to become the largest and most powerful land animals that had existed up to that point.

Keep in touch for The Coming of Mammals – Part II in which we will explore how the synapsids navigated the trials of the Permian Period and the rise of the age of reptiles.

Leave a comment